|

|

|

Alaskan

Aerial Survey Expedition

The first Alaskan

Aerial Survey Expedition was conducted between June 6 and September  24, 1926, headed by

Lieutenant Ben H. Wyatt of NAS San Diego. The preparations for the expedition

were largely made at San Diego, although the staging area was

Seattle .The last elements of the Alaskan Aerial

Survey Expedition departed Seattle for Alaska. The expedition, under command of Lieutenant B. H. Wyatt, was

composed of the tender Gannet (AM 41) the barge

24, 1926, headed by

Lieutenant Ben H. Wyatt of NAS San Diego. The preparations for the expedition

were largely made at San Diego, although the staging area was

Seattle .The last elements of the Alaskan Aerial

Survey Expedition departed Seattle for Alaska. The expedition, under command of Lieutenant B. H. Wyatt, was

composed of the tender Gannet (AM 41) the barge YF 88 housing a photo lab and mobile base for the expedition,

and three

Loening amphibians. Two of the airplanes were OL-4s equipped

for aerial photography. The third was an OL-2 which served as a standby plane for searching in

case one of the photography planes was forced down. It was also the radio plane

for the expedition.

YF 88 housing a photo lab and mobile base for the expedition,

and three

Loening amphibians. Two of the airplanes were OL-4s equipped

for aerial photography. The third was an OL-2 which served as a standby plane for searching in

case one of the photography planes was forced down. It was also the radio plane

for the expedition.

|

The Gannet! San Diego, prior to the Alaskan Survey. (Built by Todd, New York. Laid down 1 November 1918, launched 19 March 1919, commissioned 10 July 1919. Assigned to seaplane duties immediately upon completion, but also served in towing, salvage, transport and general support duties. Designated "minesweeper for duty with aircraft" 30 April 1931. Redesignated AVP8 22 January 1936. Torpedoed and sunk by U-653 off Bermuda 7 June 1942 while searching for a torpedoed freighter.) |

The w ork of the expedition, which

extended through the summer and into September, was performed in cooperation with the

Department of the Interior for early aerial mapping of Alaska.

The

purpose of the expedition was survey of Southeast Alaska for the Department

of the Interior for use with the investigation of resources of

that region.

During the summer over 15,000 square

miles

were mapped.

ork of the expedition, which

extended through the summer and into September, was performed in cooperation with the

Department of the Interior for early aerial mapping of Alaska.

The

purpose of the expedition was survey of Southeast Alaska for the Department

of the Interior for use with the investigation of resources of

that region.

During the summer over 15,000 square

miles

were mapped.

The Alaskan Survey

which began in 1926 was completed in 1929 under the command of Lieutenant Commander A. H. Radford

(Rear Admiral - whose

distinguished naval career  cumulated

in service

as Chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff l953- of Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet. The winged seal insignia designed by Lieutenant Emile Chourre was painted

was painted on the four Loening Amphibians (four

new Wasp powered OL-8As) of the S

cumulated

in service

as Chairman of the Joints Chiefs of Staff l953- of Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet. The winged seal insignia designed by Lieutenant Emile Chourre was painted

was painted on the four Loening Amphibians (four

new Wasp powered OL-8As) of the S urvey which left San Diego on May 15. Each

aircraft bore a name Juneau, Ketchikan, Petersburg,

and Sitka & bore a large Winged

Seal Insignia special id. VJ-1F l957) of Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet.

The winged seal insignia operated the Fourth Alaskan Survey - 1934

with OL-9 aircraft. (Note Radford was VJ-1 Squadron Skipper when they embarked

on the Yorktown for Pearl 6 Jun 40.)

urvey which left San Diego on May 15. Each

aircraft bore a name Juneau, Ketchikan, Petersburg,

and Sitka & bore a large Winged

Seal Insignia special id. VJ-1F l957) of Aircraft Squadrons, Battle Fleet.

The winged seal insignia operated the Fourth Alaskan Survey - 1934

with OL-9 aircraft. (Note Radford was VJ-1 Squadron Skipper when they embarked

on the Yorktown for Pearl 6 Jun 40.)

A U. S.  Navy Loening OL-8A called the

"Juneau" flown by Lieutenant Commander Arthur W. Radford on the Alaskan Aerial Survey

Detachment in Southeast Alaska in 1929. Radford went on to become Admiral

Radford, Chairman, Joint Chief of Staff.

The USS GANNET with a covered barge in tow

left from Puget Sound Navy Yard for the survey.

Lieutenant Commander Radford, who commanded the survey, was

Operations Officer of NAS.

Navy Loening OL-8A called the

"Juneau" flown by Lieutenant Commander Arthur W. Radford on the Alaskan Aerial Survey

Detachment in Southeast Alaska in 1929. Radford went on to become Admiral

Radford, Chairman, Joint Chief of Staff.

The USS GANNET with a covered barge in tow

left from Puget Sound Navy Yard for the survey.

Lieutenant Commander Radford, who commanded the survey, was

Operations Officer of NAS.

|

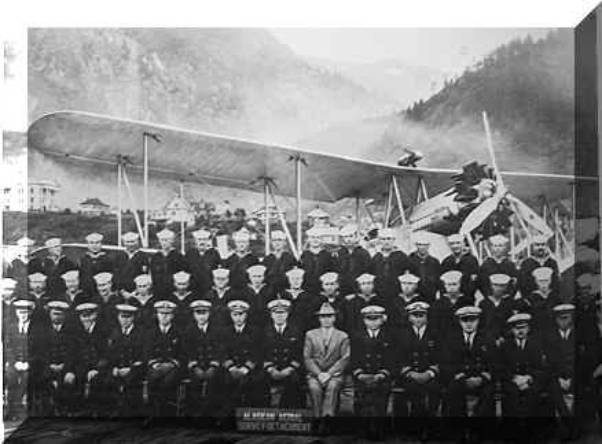

THE

GOOD (?) OLD DAYS With getting ready to celebrate 20 years of continuous

service as the records of the past years have been getting a Going over.

Here we have two photographs taken during the Alaskan survey, which the

squadron conducted in 1934. This survey and others similar to it were

partly responsible for the Navy being able to establish bases In the

Aleutians and Alaska for the war which has just ended. In the group photo the chief on the extreme left is

Hanson, ACCM, who is still in charge of the carpenter shop of this

squadron. The aircraft, which is being hoisted aboard the tender, is an

OL-9, which is the forerunner of the present day J2F's which the Navy

uses. |

THEY

MAPPED ALASKA'S WILDS

Thirty-five years ago, an expedition put out from San Diego to spend the

summer making aerial maps of unexplored territory in

Alaska.The following story of the adventure was written by Lt. Ben H. Wyatt,

senior Naval Aviator and expedition commander. It has been condensed only slightly from the way

it appeared in the February 1927 issue of World’s Work magazine.

The portions appearing in standard type are

those which were published in 1927. The paragraphs in hold face were writ ten in

this, the Fiftieth Anniversary Year of Naval Aviation, by the same author, now

Commodore Ben Wyatt, USN, Retired. The bold face paragraphs may he construed as

his afterthoughts of the expedition.

By Commodore Ben H. Wyatt, USN, (Ret.)

As

THE NOISELESS snows of Time have descended upon the eternal mountains of Alaska,

so has the inaudible foot of the Past left imprint upon our memory, which

remains as fresh as the newly fallen snows of today on those same Alaskan peaks

which challenged our efforts of yesteryear.

‘Tis

said that "the past is the prologue of Tomorrow." Since we are

celebrating the 50th Anniversary of Naval Aviation, we beg your indulgence for a

short review of those early years, so that the picture of the future may be

better developed.

The

day was gray, the clouds were low, a dead calm prevailed, when on the morning of

May 24, 1926, three heavily laden planes attached to the Aircraft Squadrons,

Battle Fleet, took the air. Swinging over the Naval Air Station at San Diego,

the planes, with their powerful motors thrumming a song, turned, assumed a

cruising formation, and headed northward, Alaska bound. They were off, embarked

on a photographic mission, the equal of which had not, as far as is known, ever

been attempted by the air forces of any nation-to survey from the air

America’s last frontier, the hitherto unexplored and almost inaccessible

islands and portions of the mainland of southeastern Alaska.

Alaska has long been famed in fiction and picture as

the land of ice and a land of saloons, and gold, and snow-the land, which has

for ages stood aloof and ignored the pleas, the struggles, and the conquering

aspirations of man. Its towering peaks, covered with the snows of ages, have

stood since time immemorial, forbidding man and his science the right to

conquer.

Alaska has long been famed in fiction and picture as

the land of ice and a land of saloons, and gold, and snow-the land, which has

for ages stood aloof and ignored the pleas, the struggles, and the conquering

aspirations of man. Its towering peaks, covered with the snows of ages, have

stood since time immemorial, forbidding man and his science the right to

conquer.

Those

words-"The Frozen North!" -flashed through my brain when I was

notified by the Navy Department that I had been placed in command of an

expedition to fly into that land of romance for the purpose of making an aerial

photographic map of its topography. At that time, Alaska was to me the Alaska of

Robert W. Service, a land of saloons, and gold, and "ladies" known as

Lou.

Immediately upon receipt of orders to command the

expedition, I set about to organize it. There was much to be  done. First and foremost, there were planes to be

selected; then cameras to be obtained, a tender to be found, and highly skilled pilots and personnel

chosen and trained. Realizing that we should have to fly over foreign territory, we had

to obtain permission from the British Embassy for the planes to operate in

Canadian waters. Since much of the territory over which the planes would be operating was uninhabited

and unexplored, it was necessary for us to gather information as to the location

of probable bases as well as to cache supplies, food, gasoline, and oil at

selected points. All of this and much more had to be arranged in a limited

period of time.

done. First and foremost, there were planes to be

selected; then cameras to be obtained, a tender to be found, and highly skilled pilots and personnel

chosen and trained. Realizing that we should have to fly over foreign territory, we had

to obtain permission from the British Embassy for the planes to operate in

Canadian waters. Since much of the territory over which the planes would be operating was uninhabited

and unexplored, it was necessary for us to gather information as to the location

of probable bases as well as to cache supplies, food, gasoline, and oil at

selected points. All of this and much more had to be arranged in a limited

period of time.

The type of plane chosen was the Loening Amphibian, which represents the very latest development in aircraft. This plane was chosen because of its ability to land either on the water or on the land. If the pilot desires to land on the land, he operates a lever, which lowers a pair of wheels, and the plane becomes a landplane. The operation of raising and lowering the wheels reminds one of the folding beds used in apartments.

This

type of plane was chosen not with the idea that it would be possible to land in

southeastern Alaska as a landplane, but rather with the thought that it could be

landed on the water and then by lowering the wheels the plane could be taxied

out of the water on to the beach where it could be securely tied down and

otherwise protected from the severe storms which sweep up and down the narrow

channels with hurricane-like force.

The

wisdom of our selection of this plane was brought forcibly to our attention

during our first month’s operations, when a very severe storm caused much

damage to fishnets and small boats throughout the entire Alexander Archipelago.

No seaplane could have possibly withstood the storm, while moored out.

As we look back 35 years and review the Loening

Amphibian which we used, our present day aviators may scoff at the crudeness of

our equipment. Certainly no seaplane of any year could have withstood the storms that swept the seas and

inlets during our stay in Alaska. No land areas were available upon which a

"landplane" could operate.

As we look back 35 years and review the Loening

Amphibian which we used, our present day aviators may scoff at the crudeness of

our equipment. Certainly no seaplane of any year could have withstood the storms that swept the seas and

inlets during our stay in Alaska. No land areas were available upon which a

"landplane" could operate.

Today with our "push button" practices,

with time and effort-saving devices,  we are far removed from the hand crank, which lowered

and raised the wheels of our planes. Though hand cranks we used, our tempers were not

abused-and our wheels were down when they should be down, and up when landing on

the sea. The

altitudes at which today’s planes fly and the range of the cameras bear the

same relationship between the hand crank of yesterday and the push button

miracles of today’s marvels. We of the Alaska Survey in our days were pioneers

in our field.

we are far removed from the hand crank, which lowered

and raised the wheels of our planes. Though hand cranks we used, our tempers were not

abused-and our wheels were down when they should be down, and up when landing on

the sea. The

altitudes at which today’s planes fly and the range of the cameras bear the

same relationship between the hand crank of yesterday and the push button

miracles of today’s marvels. We of the Alaska Survey in our days were pioneers

in our field.

Another

new feature of this plane is the fact that it is equipped with an inverted

Liberty motor. Instead of the motor being placed in the normal upright position,

it is placed upside down. That is, the pilot, instead of looking out over the

top rows of cylinders, is looking over the crankcase. The advantages claimed for

this motor are additional horsepower, owing to better cooling and lubrication;

better vision for the pilot; and a higher application of the thrust, since the

propeller is mounted on the crankshaft, which in the inverted motor is near the

highest point.

The cameras chosen were of the type known as the "Tri-Lens" and were invented by Maj. Bagley, formerly of the Interior Department. This camera, as the name implies, has three lenses, which

operate simultaneously, giving three exposures. The

center picture is a true vertical; the other two are taken at angles of 35

degree on either side. In order to use the two side pictures, it is necessary

first to transform them so as to give a projection in the vertical plane. For

this purpose special transformers have to be built for each camera. The camera

uses film, which is made in rolls six inches wide, and an average of 380 feet

long. Alaska is far removed from an aviation base, so it was necessary to find a

tender to serve the planes and pro vide supplies for the base. The USS Gannet,

a vessel of the minesweeper class, was designated to do this duty by Adm.

Charles F. Hughes, then Commander-in-Chief of the Battle Fleet. Since it was not

deemed feasible for the Gannet to

quarter the aviation detachment as well as her own crew, some means of

quartering these men in the vicinity of the airplane base was necessary. After

considerable thought and worry, the plan of quartering them ashore in tents was

abandoned because of the torrential rains and cold. Instead of tents we used a

floating, covered barge, 110 feet long and 40 feet wide. This barge was fitted

with sleeping quarters for the crew, a galley where the food was prepared, a

motor over-haul shop for the care of the plane motors, a photographic laboratory

where the film was developed immediately upon the return of the planes from a

mapping flight, radio equipment for communicating with the planes and tender

when they were away from the base, hot and cold showers, a barber shop, and all

the necessities of life as well as many of their discomforts.

The

opinion that the barge was a fine place to live in was jointly held by the crew

and the mosqu itoes.

The covered barge YP-88 met with much opposition from

the marine experts and particularly the marine pilots of Alaska. Having had a

limited sea-going experience in World War I aboard destroyers, I shared

this concern with our critics. After a thorough investigation, I made my concern

known to Admiral Hoogeworth, Commandant of the Bremerton Naval Shipyard where

the barge was being prepared. I also secured the services of the man whom I

believed to be the best Alaskan pilot available.

itoes.

The covered barge YP-88 met with much opposition from

the marine experts and particularly the marine pilots of Alaska. Having had a

limited sea-going experience in World War I aboard destroyers, I shared

this concern with our critics. After a thorough investigation, I made my concern

known to Admiral Hoogeworth, Commandant of the Bremerton Naval Shipyard where

the barge was being prepared. I also secured the services of the man whom I

believed to be the best Alaskan pilot available.

The

thorough work of the shipyard and the able handling by our pilot and Captain

Spears of the Gannet saw us through to the successful completion of our task

without incident. The barge YP-88 was mostly referred to as the "Pigeon

Roost-" Although we had radio sets in those days, they were heavy and

bulky. Since we had to get as much altitude as possible with our planes, we had

to limit their load.

Communication

by radio between two points at sea level in mountainous areas was and is very

erratic owing to intervening mountains, which trapped the passage of the radio

wave. Hence we carried homing pigeons in our planes for release in case of

emergency.

The

"Pigeon’s Roost" was on the upper after section of the roofline of

the barge as shown in the photos. Except for trial flights, the pigeons were

used on only one occasion.

We

were completing our survey for the day and were on our eastward run. In our

Flights we seldom saw any evidence of human beings or habitation. However, as we

turned westward to return home we saw someone on the leeward shore of the lake

over which we were flying. We landed and taxied to the beach. There on the shore

with a canoe snugly moored to her trim waistline was a young lady who presented

a picture requiring the talent of a master painter to match her beauty and

harmonious setting of the scene before us. Unfortunately at this moment my

attention was diverted from the shore by the disembarking movements of the

bachelor Lieutenant in the rear seat behind me.

"My

name is Whitehead, what’s yours, and what are you doing here?"

"Ketchin

foxes or any animals fit to be had . . . - Kin I do much for you folks?"

she answered. "Well, we thought maybe you were in trouble and needed our

help. Where do you live?" "Over a distance there, five miles or more,

t’other side of the lake." Dick, with a twinkle in his eyes, reluctantly

said to me, "Ben, could we tow her home if she wishes?" "Sure we

could," I said. "Load her in your seat, then you and the traps get

into the canoe. Tie it astern, and off we’ll go!"

And

this was the only use of our pigeons; to report our delay.

The organization of the expedition comprised three units-the planes, the tender, and the covered barge. The force was entirely self-supporting as well as a mobile, sea-going unit. With the Gannet as a means of transporting supplies from their permanent source and of towing the barge to

isolated sections, the only requirements for a suitable

base were an

anchorage protected from the wind and sea, a sufficient quantity of fresh water

for use in photographic work, and a beach upon which to run the planes out of

the water.

The

personnel comprised 12 officers and 100 men. The aviation detachment numbered

seven officers including five pilots, a flight surgeon, and a supply officer,

and 40 enlisted men of various ratings. The Gannet, under command of Lieutenant William K. Spear, carried her

regular crew of five officers and 60 men.

At

Seattle, after a 1300-mile journey up the coast, the planes and the Gannet

made a rendezvous at the Navy Yard in Puget Sound. Here the covered barge

was awaiting the arrival of the expedition. Aviation stores, the 40 men of the

aviation detachment with bag and baggage, commissary equipment, fresh water, and

provisions were loaded helter-skelter aboard the barge-and the long journey to

Alaska began. We were finally headed for Ketchikan, our first operating base.

Ketchikan is built on the side of a mountain and on piling over the water. Most

of the main thoroughfares are nothing more than docks built up in the manner of

streets. The entire business district is on piles with the floor a few feet

above high water.

As

we circled the city preparatory to landing in the channel—which was barely

wide enough to turn the planes in—it appeared that the entire population of

5,000 inhabitants was lined up on the docks and hillsides to give us a welcome.

As soon as we landed, we were met by so many small boats that it was necessary

for me to stop my motor and direct one of the boats to clear the way ahead, so

that we could go on to the beach. The boat led us into the dock and pointed to

an area covered with water and told us that that was the beach. At first we

thought that the Commercial Club of Ketchikan, which had written that they had a

sand beach, had sold us a gold brick. However, we went in and anchored in about

two feet of water. In about an hour we were resting on a firm sand beach, and in

two hours there appeared before our eyes a perfect hard sand beach with a

baseball diamond laid out ready for play. The range of tide is more than 20

feet.

On

the next day, while awaiting the arrival of the Gannet, I made a reconnaissance flight around the Island of

Revillagigedo (pronounced Ra-ve-yahe-ha-tho, according to the Gazetear,

and in various other ways, mostly incorrect, by the populace), and over

to the International Boundary. I shall not soon forget the feeling of awe that

overcame me on this flight. Here we were, ready to begin the aerial mapping. As

we climbed upward to 4,000 feet, 6,000, then 8,000 and 10,000 feet, and finally

we were more than two miles above sea level, and at times were passing only a

few hundred feet above the snow-clad peaks and the next moment looking down from

their dizzy heights to sea level, I realized that we had undertaken to assist in

conquering America’s last frontier.

At

that moment the task seemed hopeless. But on the arrival of the Gannet

the next day, we made our first photographic flight, starting at three

o’clock in the afternoon and ending at eight-thirty, covering about 400 square

miles of territory so rough and at places so inaccessible to man that months or

perhaps years would be required for a survey by man on foot,

In

fact, because of the ruggedness of the high country and the almost impenetrable,

jungle-like forests of the lower country, coupled with the inclement weather,

little progress had been made in this region by the ordinary methods of survey.

By the old methods of surveying, a base line had to be run with a transit and

chain, and much of the area had to be covered on foot. By the aerial method the

flyer takes his film and camera aloft, flies over the territory and takes

photographs. These are developed and then adjacent prints are matched together

and a complete picture is made which shows the entire territory under survey. It

is possible to scale this picture as accurately as any chart or, for that

matter, blue print.

In

short, an aerial survey is a picture, which shows all objects in their exact

position and size in relation to one another. The cameras are mounted in the

bottom of the plane and kept in the vertical position, so that the photographs

are taken looking straight downward. The exposures of the films are timed so

that the objects on the ground overlap on the print about 40 per cent.

In

other words, aerial mapping is nothing but a motion picture reversed the camera

does the moving while the objects photographed are stationary. The rapidity with

which an aerial survey can be made is astounding. A plane flying at 10,000 feet

above sea level making 100 miles an hour can survey a strip seven miles wide and

100 miles long—that is, 700 square miles, in an hour.

The

aerial survey of Alaska aroused worldwide interest in the use of the airplane

for topographical survey covering rugged and inaccessible areas. By reason of

the variation in the heights of mountains, the scale of the photographs is

constantly changing. It was therefore necessary to work out a "transforming

scale" to cover all land areas.

During

the  summer

of 1925, we made a survey of the U.S. Naval oil shale reserves bordering on the

Colorado River

in the vicinity

of Rifle, Colorado. The variation of the land heights there ranges from 3800 to

8800 feet. By using the negatives obtained, we were able to develop a

satisfactory transforming scale to meet the requirements of Alaska. As

a result of this survey we were asked to attend and present a report on our work

to the International Photogrammetric Conferences in Switzerland and Germany.

summer

of 1925, we made a survey of the U.S. Naval oil shale reserves bordering on the

Colorado River

in the vicinity

of Rifle, Colorado. The variation of the land heights there ranges from 3800 to

8800 feet. By using the negatives obtained, we were able to develop a

satisfactory transforming scale to meet the requirements of Alaska. As

a result of this survey we were asked to attend and present a report on our work

to the International Photogrammetric Conferences in Switzerland and Germany.

Only

two of the planes were used for mapping. The third was equipped with a radio

and, with a pilot, was kept on the beach, in readiness to institute search for

any plane that might fail to return to the base within 45 minutes of its

schedule. Prior to the departure of a plane for a flight, the exact area,

courses, and routes were laid down on flight lines over the chart so that the

position of a missing plane could be fairly well approximated, in the event it

became necessary to search for it. All planes carried emergency rations for five

days, guns, ammunition, fishing tackle, smoke flares and homing pigeons in case

of a forced landing. Fortunately, it was not necessary to resort to any of our

emergency kits since no forced landing from any cause whatsoever occurred.

Not

all of our time was spent in work. There were fishing and hunting trips. The

mountains of Alaska abound in big game and constitute a hunter’s paradise. The

Alaska Brown Bear is said to be the fiercest flesh-eating animal in North

America. This, no doubt, would be a pleasant thought to the pilot and crew as

they were plodding their weary way homeward after having been forced to land by

motor failure on a snow-clad mountain peak a hundred miles or so from their

base. Our contact with the bears, however, was not limited to the stories told

us by the natives. The sentry standing watch on the planes one night looked up

from his fishing and suddenly discovered a husky fellow making inroads on his

catch. When questioned later he was unable to state whether the intruder was a

black or a brown bear. He didn’t wait to see.

Of

fish there were plenty. Captain Spear on his last fishing party brought back 300

good-sized trout. For my part, however, I felt that if some local Burbank should

cross the fish with the mosquitoes I should stand a better chance of getting a

bite.

The

Alaskan mosquitoes are industrious, ambitious, and successful. There is also

another pest, in the nature of a gnat, which inhabits the woods and is so small

that the Indians call them "No See ‘Ems." Many of my shipmates,

being men of intelligence and reason, believe only what they see, but I,

intelligent or not, believe in them.

Little did I know that my encounter with the

mosquitoes and gnats in Alaska was merely a training course for the experiences

to follow. Soon and

operation of their aviation activities we engaged in photographic surveys

extending from the Pacific coast across the Andes and to the upper headwaters of

the Amazon River and along the river to Iquito’s. Throughout all this region,

the steaming tropical jungles were infested by the malarial mosquito and every

pest that flew, ran, crawled or swain.

Little did I know that my encounter with the

mosquitoes and gnats in Alaska was merely a training course for the experiences

to follow. Soon and

operation of their aviation activities we engaged in photographic surveys

extending from the Pacific coast across the Andes and to the upper headwaters of

the Amazon River and along the river to Iquito’s. Throughout all this region,

the steaming tropical jungles were infested by the malarial mosquito and every

pest that flew, ran, crawled or swain.

Then,

during WW II with our Pacific carrier groups in the Guadalcanal area and later

as Commander of the Central Pacific Islands, I engaged in a combination mosquito

and pest contest—in which, despite the advent of DDT and all its allies, the

mosquitoes emerged victorious. So, today, as we did in Alaska, I reaffirm my

belief in the might of the mosquito.

Much

time was lost owing to low clouds and rain. An aerologist attached to the

expedition kept a weather log, prepared a daily weather chart, and issued

forecasts. However, the aerologist met with keen competition in the matter of

forecasting weather. The native Indians have considerable weather lore, which

they fall back upon when forecasting. One of the old Indians who frequented the

operating beach was very accurate in his estimates. He claimed that the ravens

change the tone of their cry with a change of the weather. Another one told us

that when the sea gulls come in and hover over the mountain the winds are going

to be strong from the southeast and will bring rain.

Many

of the steamship captains have given up the hope of forecasting the weather and

close the question by saving "You never can tell." Experience with the

weather chart, however, has indicated that it is just as easy to forecast

weather along the southeastern section of Alaska as it is elsewhere along the

Pacific Coast. Certainly the forecaster will make a far better record than the

average, should he forecast daily, "Rain today and tomorrow."

From

Ketchikan we worked our way northward, shifting our bases as the necessity

arose, taking in the entire area from the International Boundary on the south to

the Canadian Boundary on the east and the Pacific on the west. At times the

weather was discouraging - it seemed that it would never stop raining. When the

weather was clear much progress could be made. Our average day’s work for two

planes was better than 1000 square miles. On two successive days, 1600 square

miles each day were surveyed.

As

one area was finished the Gannet would

tow the barge and supplies to our next base. The planes as a rule would proceed

with mapping and, upon completion of the work, fly to the newly selected base.

Obtaining gas and supplies was quite a problem. While engaged in mapping, the

planes consumed more than 600 gallons of gasoline per day. When the good weather

did arrive, it usually lasted for about ten days, so that our plans had to be

laid well in advance to prevent any delay in mapping operations.

We

were fortunate that not one day of mapping weather was lost for any cause

whatsoever—nor was any plane out of commission when it could have been used

for mapping.

During

our summer’s work many new lakes were discovered—the power of which no doubt

will be used to turn the wheels of industry when the time comes to develop the

tremendous resources of Alaska. Millions of acres of invaluable timber were

brought to light—timber for the manufacture of pulp and paper—and much

airplane spruce. The famous and treacherous waters of the Chickamin River, down

whose shores have washed the richest and most valuable gold deposits in America,

were thoroughly explored and mapped.

We

surveyed the chain of glaciers throughout the northern rim of the Alexander

Archipelago whose great ice caps tower upward to heights as great as 15,000 feet

and end abruptly in great precipices miles in width and hundreds of feet high at

the water’s edge. These great glaciers are remnants of the Glacial Age. Some

are still alive today—moving slowly but surely a few feet a day, throwing off

huge icebergs, which fall into the sea with the roar of thunder.

In

our crew we were fortunate to have Mr. Sargent, a representative the Department

of the Interior. He was a gentle, quiet man of wisdom and understanding. Being

the oldest in Our Crew, he was our counselor and advisor; in return lie received

our thanks and respect.

To

him there was no task too difficult, no mountain too high to climb, no glacier

too slippery to scale. As we worked northward in our survey he constantly

reminded me that we should "cover Glacier Bay and get some scaled photos of

Muir Glacier and Mount Fairweather," which rose at the base of Muir Glacier

at the head of Glacier Bay and continued on to the westward slope where it sank

into the Pacific.

Mount

Fairweather is the southern extremity of the northwestern mountain range

extending from Glacier Bay in the south to the Seward Peninsula in the north.

This range forms the western barrier of the North American continent where the

storms that sweep with violence out of the Bering Sea set their course en route

to the United States mainland.

Mount

Fairweather rises to a height about 15,000 feet. Our planes, lightly loaded,

could reach 15,000 feet at most. "how, then, Mr. Sargent, can we make a

scaled photo of Mt. Fair-weather?" we asked.

"Let

us go to the laboratory and work out a method," lie said. "At any

rate, let us try it." And try it we did. Our efforts repaid its by the

results obtained. They incidentally led to the discovery of what was later

termed ‘‘the Preglacial Forest.’’ I believe it of sufficient interest to

describe briefly its discovery.

Our

interest in the survey was the Glacier and the upper slopes of the mountain on

the southern exposure. The normal wind, which brings fair weather in that area,

was from the northwest. What we needed was a southeast wind to give us the

upward flow of air on the south side. A southeast wind, however, brought clouds,

which prevented photography.

A

detailed study of the weather conditions indicated that a period of five hours

of clear weather might well prevail after the reversal of the wind currents from

northwest to southeast. With the weatherman embarked on our tender, the Gannet,

anchored in Glacier Bay, we were lucky in our calculations and arrived on

location with a fair southeast wind and clear skies.

We

flew a carefully measured zigzag course from the end of the glacier at the head

of the bay and gradually role upward on the rising air currents until we had

covered the entire southern section.

When

we developed the negatives, an examination of our prints showed occasional black

spots at irregular intervals along the entire lower section of the glacier. This

interested all of us.

Mr.

Sargent, after studying many pictures, said to us: "These are trees,

that’s what they are!" "Well, let’s say they are trees, what of it

?" I countered. "I’ve seen igloos covered with snow and ice."

"But, Ben, you don’t realize that the snow and ice of that glacier have

been there for a million years or more—and those trees, if trees they are,

were there growing before the glacier was formed.

"These

glaciers are remnants of the second Glacial Age. Most are dormant as this one

and gradually disintegrated - and maybe we have discovered a forest, which, if

so, is a ‘Pre-Glacial Forest.’ "

"All right, Mr. Sargent—what do we do about it?"

"We

send an expedition in there to examine it and find out about it."

"O.K.,

it’s your project. Name your leader, pick your men, outfit them, and we’ll

settle this argument."

We

did. Mr. Sargent led a group of hale and hearty young men (he was, I presume,

around 50), and returned with sections of logs from the "PreGlacial Forest

of Glacier Bay" which are "more than one million years old."

The

trees are not petrified; but preserved in their natural form with the snow and

ice that fell and froze during the "second glacial age." My souvenir

is a small section of a log said to be of the pine family, and it is still well

preserved.It is my understanding that the Smithsonian Institution has some of

Sargent’s samples and that lie turned a report of the "Pre-Glacial

Forest" into the Institution.

On

the island of Revillagigedo, a valley and low pass were discovered which in the

opinion of Charles H. Florey, the Alaskan District Forester, will permit the

linking up of all the important water power sites of Revillagigedo with the

mainland and deliver more than 85,000 horsepower to the city of Ketchikan.

Our

work, aside from proving the feasibility of surveying by aircraft, was an acid

test on the airplane itself, and it proved its ability to operate for long

periods of time away from the home base under the most severe climatic

conditions and with little or no protection from rains, storms, and seas. After

the completion of the summer’s work, the planes were flown back to San Diego

and were ready to begin operations with the Fleet on the day of their arrival.

The

dramatic, eternal landscape of Alaska, the rugged, forbidding, snowcapped

mountains, suddenly and abruptly turning to the calm and glistening emerald of

an ocean inlet, the furious and fast moving billowing clouds that suddenly burst

with torrential rain or snows, followed by the rainbow that reveals the

landscape in all its glories of ageless ice and snow - all of these we well

remember. However, indelibly engraved upon our thoughts is the cordial

friendship we received a comforting and enduring gift of the people of Alaska.

In

September, 1935 the second Alaskan Aerial Survey expedition was sent to Dutch

Harbor in the Aleutians to do Additional aerial mapping of uncharted areas.